17 avril 2025

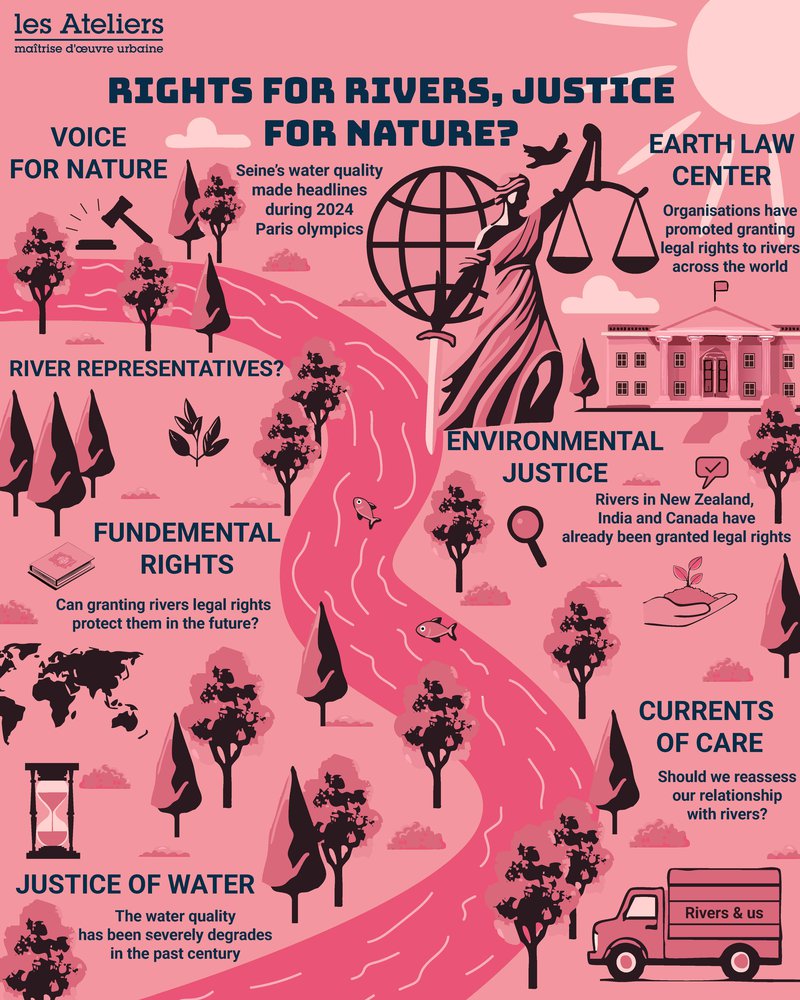

Should we give rivers legal personhood or legal rights?

The article below may be downloaded at the bottom of this page. The attached file also includes all the references quoted in the article.

When the Olympic and Paralympic Games came to Paris in 2024, one of the primary projects of the games and its legacy in the region focused on an eventual €1.4bn project to clean-up the River Seine (Ville de Paris 2024). This followed a century of swimming in the river being banned. During the Olympic and Paralympic Games themselves, it was also a significant location, with several Olympic and Paralympic events taking place on the river (Triathlon, Marathon Swimming and Para-Triathlon). Moreover, the Opening Ceremony of the Olympics saw athletes floating down the Seine, passing the many famous Parisian landmarks along its course. Nonetheless, in the long-term, the project to clean-up the Seine envisioned swimming areas “along the Seine at the Bras Marie, Bras de Grenelle and Bercy” that would be accessible to the public for generations to come (EEA 2024).

Despite this, the Seine became the centre of some of the prominent stories of the games for the wrong reasons, with concerns over the pollution of the river raised before the first athlete entered the river. Whilst these concerns were attributed to the existing drainage system that predated the clean-up process, the consequences of the pollution impacted the Games and made headlines across the planet. Both the first event on the river during the Olympics and the Para-triathlon events during the Paralympics were postponed due to the high levels of E. coli present in the Seine when tests were done prior to the scheduled start of the events (Lofthouse 2024) (Smith 2024) (FitzGerald 2024). Although all these events would take place following better water quality results, the delays reinforced questions and concerns about the future of public swimming in the river. Moreover, could the additional pressure of the project having to be finished in time for the 2024 Games have been mitigated by a relocation of these events which, according to Lambis Konstantinidis, the operations director for Paris 2024, was possible (Lofthouse 2024)?

It seems obvious to ask more generally what should be done in order to resolve these issues and dilemmas in terms of (1) what is being done, (2) what needs to accompany this work and (3) how can it be maintained into the future? These concerns are the focus of the rest of this piece.

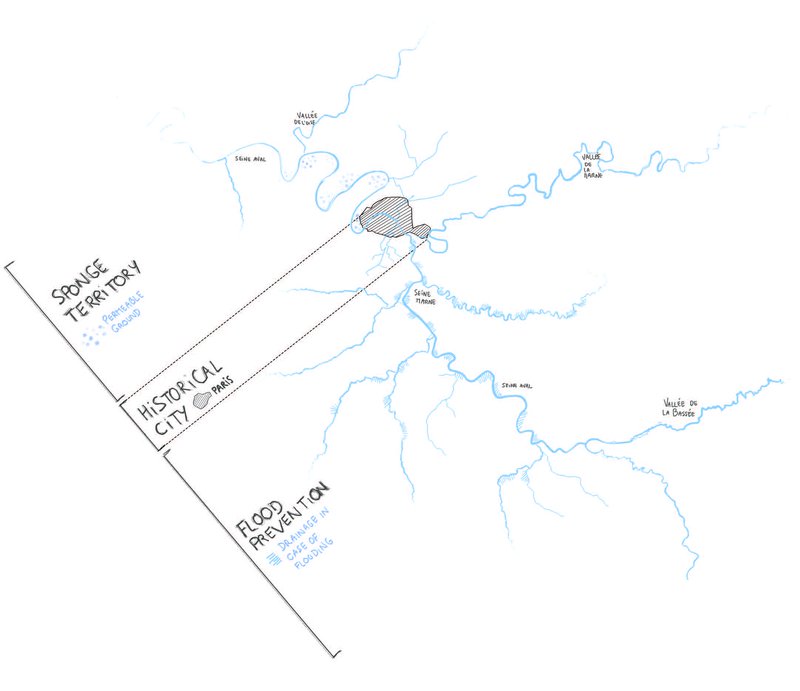

In the case of the Seine, regeneration and restoration will be central to efforts made to improve the basin. With more than 18 million inhabitants living in proximity to the rivers’ course from Source-Seine to Le Havre (roughly a quarter of the population of France), its course is already of significant social importance to the country (Les Ateliers 2025). However, as the estuary of the Seine receives 30% of the discharge of the total French population as well as 40% of discharge from national industry, mass human activity and an overreliance on the Seine has come at a large cost to the ecological health of the river (Les Ateliers 2025). Naturally, these factors contributed to the issues at the heart of the headlines surrounding the Seine during the 2024 Paris Games.

As a result, the questions being raised at the Les Ateliers workshop are timely, both in terms of being an exploration of the same river which generated such massive attention within the last year but also as an opportunity to analyse these issues and contribute to the efforts to tackle these issues. The Seine is not the only river being subjected to the issues that climate change and human activity have contributed to, all rivers encounter the same issues. However, an analysis of one of Europe’s most well-known rivers offers a candidate for this workshop a rewarding opportunity to address the pertinent issues and consequences of a changing climate in the modern and future world. A world where, according to Climate Central’s projections on the River Seine, most of the Seine’s (lower) course between Rouen and its mouth at Le Havre is expected to be under the annual flood level as well as below 1 metre of water (Climate Central).

In order to respond to these issues, we need to consider what is crucial to a proposal focused on how we can improve and preserve the quality of water in the short and long-term. First, scientific facts and illustrated proposals are significant in analysing and planning a proposal that is informed by such information and can thus have a positive impact. Furthermore, the importance of recognising how ‘human activities are so large nowadays that they override natural processes’ is significant in any approach to the study of the future of rivers (Flipo et al. 2021:2). In the case of the Seine specifically, the success of the clean-up project relies on how it addresses and improves existing infrastructure as well as attempting to diminish all activity which has contributed to the poor ecological health of the river. It must address how “water quality has been severely degraded in terms of oxygen levels, ammonia and nitrate concentrations” as well as the presence of “bacteria over a section of river extending from 100 to 250 km downstream from Paris” if it is going to have a positive impact (Flipo et al. 2021:7). These aspects all point towards the importance of a multidisciplinary approach is addressing how we are going to improve the quality of water in rivers such as the Seine as well as preserving it in the long-term.

Due to this, I will now explore a philosophical proposal on how to contribute to the long-term preservation of the Seine Basin from reconfiguring our relationship with the Seine. This will focus on the question of whether we should grant rivers legal personhood to address and resolve these challenges.

We might consider granting legal personhood to a river as a type of environmental personhood where we confer a river the ability to exercise its rights in accordance with existing law. These may include the ability to “sue, own property, and enter into contracts” (Suresh 2023). This could be successfully implemented, for instance, by appointing “representatives with a legal responsibility to “speak for” the river in decisions about water use” (Strang 2020:206). The concept of river ‘personhood’, as to speak, emphasises a reconfiguration of the existing relationship that humanity has with rivers and river ecosystems (which I will speak about later). This may involve an expectation to maintain the quality of the river in terms of both a collective clean-up project, such as the one undertaken for the 2024 Paris Games, as well as a personal obligation to not throw fast food into rivers on an individual level.

Granting rivers legal personhood as a way of producing a long-term plan to preserve the river Seine can be considered as part of a proposal, or at the very least can inform one. This is demonstrated by how several rivers across the world have been granted legal rights as part of an effort to improve the welfare of these rivers and to promote sustainable use. These include the River Amazon being granted rights by the Colombian Supreme Court in 2018 as well as the Magpie River in Canada in 2021 (Bryner 2018) (Berge 2022). More recently, the Scottish Parliament has been considering a petition to ‘Grant Scottish rivers, including the River Clyde, the legal right to personhood’ since December 2024 (The Scottish Parliament 2024).

Granting legal personhood to rivers has been part of the mission of the Earth Law Center and its belief in “aligning our laws with Nature’s laws” (Earth Law Center). The organisation developed the ‘Universal Declaration of the Rights of Rivers,’ eventually including 9 premises, of which premise 3 established that “all rivers shall possess, at minimum, the following “fundamental rights”:

(1) The right to flow,

(2) The right to perform essential functions within its ecosystem,

(3) The right to be free from pollution,

(4) The right to feed and be fed by sustainable aquifers,

(5) The right to native biodiversity, and

(6) The right to regeneration and restoration;”

(Earth Law Center 2017:2-3)

Granting rivers across the world these “fundamental rights” will allow for the development of legal systems which can hold us more to account for our impact on rivers (Earth Law Center 2017:2). If someone or a group infringes on these rights, then we can use these rights to uphold justice for the river as well as the ecosystems it is a part of. Moreover, by granting rivers “legal standing in a court of law” as “living entities”, as premise 2 suggests, we also see a change in the previously unquestioned relationship between humans and rivers (Earth Law Center 2017:3). Instead of allowing humans to believe their rights should always be prioritised over rivers, the Earth Law Center encourages the view that rivers and humans co-exist on “our shared planet” (Earth Law Center 2017:2). Thus, it seems logical to focus on the “best interests” of a river in decision-making about rivers and river ecosystems (Earth Law Center 2017:3).

Moreover, the declaration also allows for the development of a river ethic. Whilst we have seen a development of an environmental ethic or an animal ethic, a ‘river ethic’, as to speak, is still emerging as an individual idea and is thus still malleable as an ethical concept. Nonetheless it should begin with, as Veronica Strang pointed out, moving on from an “anthropocentric belief that humans are the ‘brains of the planet’” or as “mere assets [..] for human purposes” (Strang 2017:212) (Strang 2020:204). The view that rivers and other “non-human beings” are “co-inhabitants” with humans rather than “assets” provides a framework for which the relationship between humans and rivers can be less damaging for the latter (Strang 2020:204,206). It should also recognise how rivers must be considered important even when removed from any human factors which may influence a policy or ruling.

The concept of river personhood makes it obvious that we should not consider rivers as simply carriers of sewage or places to throw our waste in. If we continue to apply an anthropocentric belief to rivers and the environment, would this be ethical? The answer to this question, in the context of my exploration of river personhood here, seems obvious that it would not be.

So how would a river ethic achieve this?

Ultimately, the creation of a river ethic, in the words of Zhang et al., “necessitates a shift from altering and conquering nature” to “adjusting human behaviour and rectifying past mistakes” in order to improve the “human-water relationship” for our contemporaries and future generations (Zhang et al. 2025:23,22). A river ethics would involve looking at how we reached this point in our relationship with rivers, exploring how our attitudes towards rivers have been shaped throughout history, responding to these attitudes and then applying the ethic to proposals concerning future water use. Thus, when we address the issues facing rivers, from the discharge and waste to the sustainability of the ecological health of the rivers in the future, the development of a river ethic is part of the solution.

As a result, shifting attitudes towards where responsibility lies for addressing these questions over climate change and the future of rivers is clearly required from a river ethic. This also helps to provide a framework for how humanities can participate in multidisciplinary projects on rivers and other environmental issues. In this case, it involves taking the lead in how we “re-imagine the river” for future generations, beginning from an ethical and legal perspective before applying it to other disciplines (Strang 2020:206).

Returning back to the Seine Basin and Les Ateliers, the workshop being held by Les Ateliers this September (September 1st to September 19th 2025) looks for candidates interested in developing a collective proposal aimed at addressing the following questions:

- How can our territories ensure the long-term preservation, accessibility, and quality of water in the Seine watershed and its tributaries?

- How does our relationship with water reconfigure our territories and lifestyles to address the major challenges of this century, at both the Seine and local scales?

- What renewed relationship can be established between the river, its tributaries, and our human activities (energy, food, mobility, leisure, etc.)?

As I hope to have shown, responses to these questions involve the input of every discipline despite the fact that I have primarily focused on the role of humanities subjects, primarily philosophy, in contributing to the future of rivers. The more variation in disciplines represented at the workshop by candidates, the more substantiated and enriching the proposals made at the workshops become. Everyone has something to contribute to resolving the issues presented by these three questions because everyone is impacted by the consequences of our “artificial interference” in ecosystems (Zhang et al. 2025:25). Irrespective of whether you live in the catchment of the River Seine, or even if you ever see visit the Seine, it is important that everyone can put forward a vision for the future of rivers as the analysis done of the Seine is applicable to all rivers.

15 candidates will be selected to be part of this year’s workshop. The workshop gives as much to the people who participate in it as it does to the local officials who receive these proposals and implement strategies and policies based on them. Consequentially, the Seine Basin, its population and the future of rivers alike the Seine benefit from your input!

For more information and to register, please visit the information page for this workshop at https://www.ateliers.org/en/workshops/243/

George Porter

A 1st year Philosophy (BA) student at the University of Warwick.